Essential Strategies for Balancing Work and Life in Construction

Editorial Note: This article was brought to you courtesy of Rose Morrison, managing editor of ...

The pandemic has caused a “once-in-a-century” exodus out of the cities as wealthier residents and remote workers seek less-expensive housing elsewhere.

Yet everywhere, the price of homes continues to soar, housing supply is at an all-time low, and new construction is unable to keep pace with record high demand. Building new homes might seem like a no-brainer, but it can actually make things worse if we continue to stick with that most notorious model of American living: the suburbs.

The suburbs continue to expand at a rapid pace all over the world, eschewing the wisdom that human civilization needs to grow up instead of out. As more people flee to the suburbs once again, we have an opportunity to take a clear-eyed look at the negative effects that suburban sprawl has on both people and the planet.

Thankfully, there are many ways that we can retrofit our suburbs to make them more affordable and more sustainable places to live.

In this article, we will offer a working definition of the suburbs and the sprawl that they create. We will also provide a brief history of where this ongoing experiment in American living came from (we promise, you’ll be surprised). Then we will discuss a few of the negative effects of suburban sprawl and take a closer look at some of the creative solutions that have been proposed to change course for the better.

“The United States has thus far been unique in four important respects that can be summed up in the following sentence: affluent and middle-class Americans live in suburban areas that are far from their workplaces, in homes that are their own, and in the center of yards that by urban standards elsewhere are enormous.”

- Crabgrass Frontier by Kenneth T. Jackson (1985)

In the United States, the suburbs are so thoroughly stamped upon the land as to be almost invisible, their existence a self-defining cul-de-sac so widespread and matter of-fact that asking about them is like asking a fish “how’s the water?”

More than half of Americans say they live in the suburbs. But what is a suburb? It is in spite or perhaps because of their ubiquity that answering this question can be difficult.

The common understanding is that suburbs are residential areas that exist on the fringes–or within commuting distance–of larger urban centers; hence the name “sub-urban.”

Right off the bat we run into the problem that not all suburban communities fit this description. Many modern suburbs actually exist as free-floating housing developments, some even in rural areas (categorized elsewhere as exurbs), completely disconnected from any central metropolitan core.

Another wrinkle is that the boundaries of cities are constantly changing. As cities balloon and bleed into one another to become megacities, the distinctions between what sits within and outside of their borders is largely a question of political imagination.

The paradox of the suburbs is how they stand both in close relation to and sharp contrast with the city, a compromise between the countryside and the skyline. While tricky to pin down, suburbs are nevertheless recognizable by a few key characteristics, wherever they might be found.

“Sometimes I wonder if the world's so small

that we can never get away from the sprawl…”

- Sprawl II by Arcade Fire (2011)

Suburban sprawl refers to the constant outward expansion of the suburbs, seemingly without plan or design, into the natural and agricultural settings that surround them.

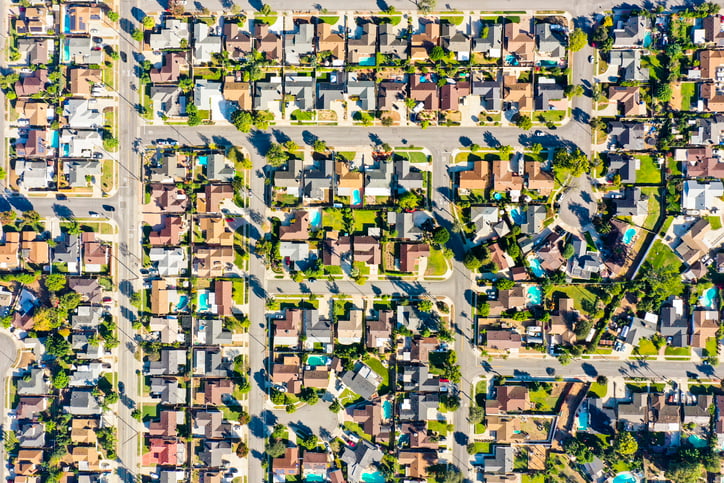

As subdivisions and strip malls spread unchecked into the countryside, so too proliferate the networks of roads and highways that connect them. Alternately referred to as urban sprawl, some prime examples of this phenomenon include Phoenix, AZ; Atlanta, GA; and Los Angeles, CA.

Standing in the middle of the sprawl, what we see is a place shaped more for cars than for human beings; an amorphous, undifferentiated landscape of cookie cutter houses, commercial zones, and concrete surfaces that stretches in every direction; an endless built environment that from the looks of it appears to have completely overtaken the natural one.

“It seemed to him, just for a second, that he could feel the whole Sprawl breathing, and its breath was old and sick and tired, all up and down the stations from Boston to Atlanta…”

- Count Zero by William Gibson (1986)

The history of the suburbs runs deeper (and stranger) than you might think.

Associated with the American Dream, capitalism, and the expansion of the frontier, it’s ironic that the genesis of the suburbs can be traced in part to an early strain of socialism from the 1800s...

The American suburb was dreamt up during the industrial revolution of the late 19th Century, as Benjamin Ross highlights in his book “Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Urbanism.”

Hoping to escape the harshness of city life and inspired by the writings of French socialist thinker Charles Fourier, groups of well-to-do landowners began building and living in phalansteries, an early type of planned community that laid the conceptual groundwork for what would eventually become the modern American suburb.

Similar to the idealistic megastructures of the 1960s, these self-contained enclaves were utopian experiments in communal living that attracted a variety of odd characters, including free love enthusiast Albert Brisbane, celebrated author Nathaniel Hawthorne, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and revered transcendentalist intellectuals Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

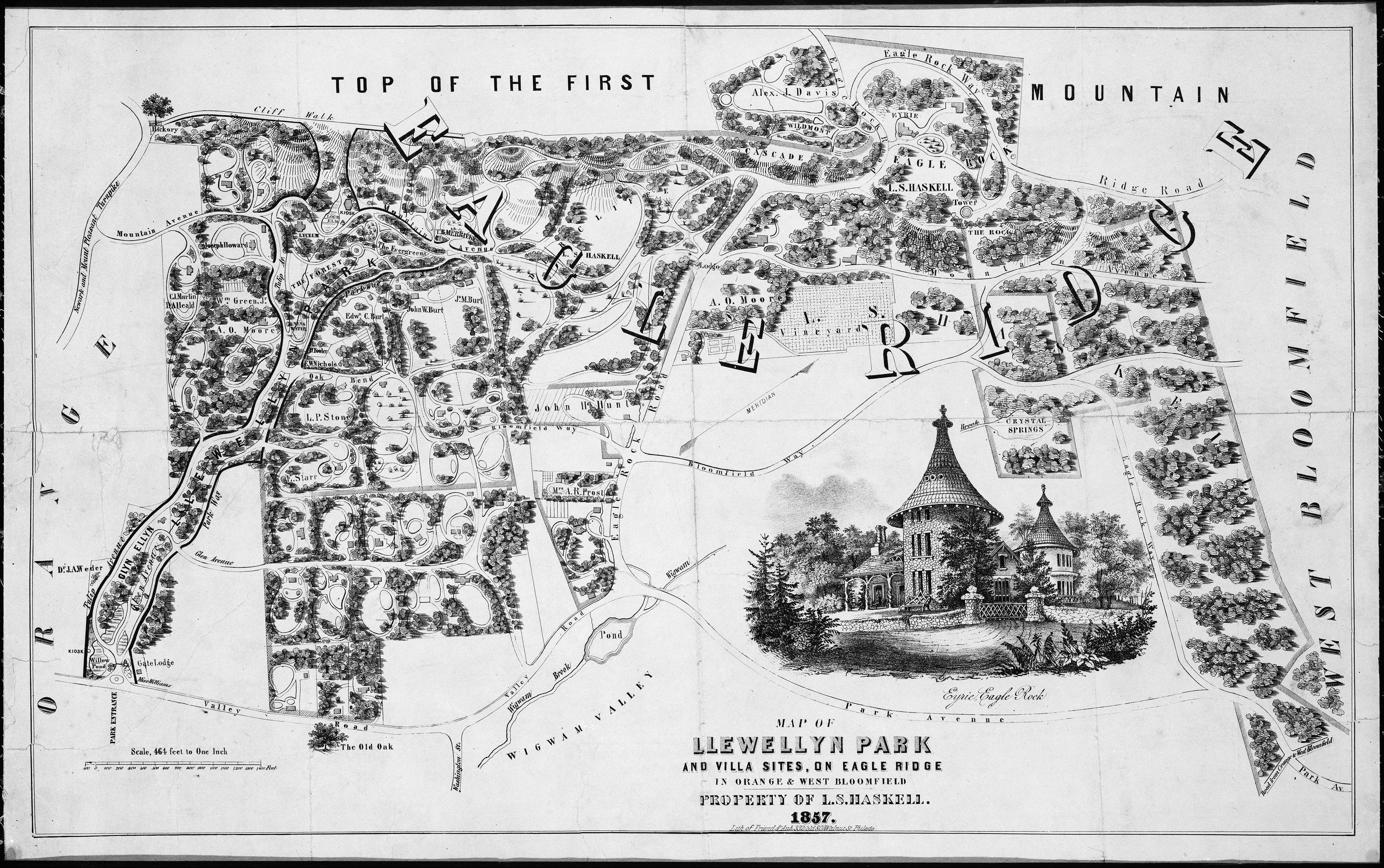

Despite their failure, the utopian allure of the socialist phalansteries carried on, morphing into a capitalism-friendly form that directly influenced the design of some of the earliest examples of suburban-style living, including Raritan Bay Union and Llewellyn Park, both founded during the 1850s in rural New Jersey.

Image Source: WikiCommons

The resultant model of single-family homes, restrictive covenants, carefully plotted lawns, and separately zoned business and industrial districts remains largely unchanged in the suburbs of today.

Primarily havens of the wealthy, the suburbs fanned out over the ensuing century with the arrival of the railroad and streetcar.

The spark that set off the first explosion of suburban sprawl was ignited after World War 2 in an era of unmatched economic prosperity that saw the creation of the middle class, the Federal Housing Administration, the advent of the American interstate system, a revolution in construction processes, changes in land use, and a plethora of mortgage loan subsidies for returning soldiers.

Though modern suburbs have gradually become more racially and economically diverse, the decades following World War 2 would see a resurgence of “white flight,” racist redlining policies, and a strengthening of exclusionary zoning practices, all of which served to shape the American suburbs into places that were overwhelmingly hostile to anyone who wasn’t white.

What we’re left with in the post-war present is an American landscape forged almost entirely out of mass suburbanization:

In 1944, annual housing starts sat at about 142,000. By the 1950s, an average of 1.5 million new homes were being built every year.

“…And so, each day, several thousand more acres of our countryside are eaten by the bulldozers, covered by pavement, dotted with suburbanites who killed the thing they thought they came to find.”

-The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs (1961)

Nowadays, most urban thinkers agree that we went wrong somewhere along the way in our development of the American suburb. The ugliness of suburban architecture is an easy (and hilarious) target, but criticism of the suburbs runs deeper than what meets the eye.

Below, we discuss 5 suburban sprawl causes and the associated problems they manifest:

The suburbs eat up a lot of land, paving over natural ecosystems and threatening global biodiversity at an alarming rate. If left unchecked, one recent study predicts that suburban sprawl will swallow up 290,000 square kilometers (about 111,2000 square miles) of additional land by 2030, an area larger than the entire United Kingdom.

A prime example of a once vibrant ecosystem that’s been decimated by suburban sprawl is the Everglades, a massive tropical wetland in South Florida that spans an area of 18,000 square miles, half of which has been drained and overtaken by the suburbs. Restoration efforts are underway, as experts fear that further incursion into the Everglades will jeopardize the drinking water the wetlands supply for the region’s 9 million residents.

Suburban households emit roughly 8% more carbon dioxide than those who live in the city. Scientists have also shown that population growth in the suburbs causes spikes in CO2 emissions that don’t occur when cities undergo comparable growth spurts.

Roughly 20% of the United States’ total carbon dioxide emissions come from homes, and about half of that amount comes from homes located in the suburbs. Fossil fuels consumed for the heating, cooling, and powering of comparatively larger suburban residences accounts for some of this but another significant source of emissions is cars. Unlike cities, which can be walkable or offer robust public transportation, the suburbs rely heavily on cars, which each emit about 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide every year.

The many paved surfaces in the suburbs absorb and re-emit high amounts of heat, raising the ambient outdoor air temperatures and increasingly transforming them into urban (or rather suburban) heat islands. The problem has raised alarms in places like Western Sydney, Australia, where over-developed, lower-income suburbs have become as much as 4 degrees hotter than the nearby city in recent years. Extreme temperatures in the age of climate change are no trivial matter: The heat kills more than 5 million people worldwide every year, and global warming is expected to make it worse.

A recent report by the Environmental Integrity Project estimates that roughly 50%of all waterways in the US are too polluted to fish, swim, or drink from. The main source of the pollution? Farms and–you guessed it–suburban lawns. Rather than being absorbed into the soil, the toxic chemical fertilizers used in suburban lawncare often end up washing down storm drains and into the drinking water supply.

“ The long drive into the sprawl has reached a dead end. America needs a train to carry it back out.”

- Dead End: Suburban Sprawl and the Rebirth of American Cities by Benjamin Ross (2014)

So, what are we going to do about this? The suburbs are bad, but let’s get real: Demolishing them and starting from scratch isn’t something we’ll be doing any time soon. The truth is (for now, at least) the suburbs are here to stay. What we have to ask ourselves now is what can we do to make them better?

Thankfully, we’re not the first ones to ask that question. New Urbanist proponents Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson are the co-authors of “Retrofitting Suburbia,” a popular book that showcases a variety of solutions for combating sprawl and making suburbs friendlier to people and the environment.

Their approach to suburban retrofitting follows three main strategies:

The thinking goes like this:

Re-inhabiting vacant buildings is more environmentally friendly than building brand new ones (it can take 10 to 80 years to offset the carbon emissions generated during new construction, even for green buildings). We can also dramatically decrease auto-traffic by re-developing suburbs to accommodate pedestrians, public transit, and higher-density housing mixed with local businesses. Finally, we can begin to reverse some of the environmental damage caused by suburban sprawl by re-greening greyfields and restoring vital ecosystems to their former vibrancy.

Here are a few of the tactics that Dunham-Jones and Williamson have proposed for retrofitting suburbia:

Dead shopping malls and abandoned big box stores are staples of suburbia, but demolishing them is incredibly wasteful. Instead of replacing them with new structures, one of the best ways to curb sprawl is to give these hollowed-out behemoths a second life through adaptive reuse, transforming vacant shopping malls and big box stores into apartments, homeless shelters, high-schools, libraries, and more.

Pictured above: Concept Art of "The Offset House" by Other Architects of Australia

Humans can work in partnership with nature instead of against it. We can repair some of the damage that the suburbs have caused by perforating the sprawl with greenery in the form of community gardens, public parks, wildlife preserves, and ecosystem restoration areas. Waterways and wetland ecologies, for example, provide biodiversity, clean drinking water, and natural stormwater management.

Exclusionary zoning codes are largely responsible for suburban sprawl, mandating sidewalk-free streets, enforcing single-use housing, and separating residences from businesses in widening strips that eat up the land and solidify the supremacy of the car. Local governments can change this paradigm by adopting more inclusive zoning codes that encourage the creation of a variety of housing options in mixed-use areas where businesses, residences, and apartments are mingled together instead of separated over large distances.

The suburbs are plagued by overly wide streets that take up needless amounts of space and prioritize cars. We can make the suburbs friendlier to pedestrians and bicyclists by shrinking the roads, widening the sidewalks, and getting rid of overly capacious setbacks. This comes with the added benefit of making more room for buildings. In his book “City Comforts,” David Sucher identifies three rules for making blocks more walkable: Build all the way up to the sidewalk, be sure to install inviting windows and entrances, and no parking lots allowed in the front of buildings.

Public transit options like buses, trolleys, and light-rail can be introduced to get suburban drivers off the road, with bike lanes and walking paths serving a similar function. A new sidewalk or bike lane isn’t all that useful, however, if it doesn’t link up with the wider transportation network. To truly make our suburbs less dependent on cars, people need to be able to traverse the length and breadth of their communities without having to get behind the wheel. We can achieve this by beefing up public transportation options and weaving comprehensive networks of bike lanes and walking paths throughout suburbia.

As we’ve already touched on, the suburbs have historically privileged wealthier white people in owner-occupied, single-family homes. Though redlining has been technically illegal since the late 1960s, its scars have lingered and housing discrimination remains a barrier in communities all over the US. One thing the suburbs can do to increase racial and income diversity is to diversify the types and affordability of housing options that are available within their borders. By embracing affordable homes and apartments, the suburbs can become more inclusive, higher-density, and more efficient in their land-use.

Sustainable construction and cutting-edge digital technologies like the IoT and AI framework behind ONE-KEY can ensure that the human-centric communities of tomorrow are smarter and greener than ever before.

Looking around, suburban sprawl can sometimes feel like an immutable law of nature instead of what it actually is: a choice.

The suburbs are what they are today because of a long history of choices made by human beings in positions of power. The past is heavy and the world troubled, but we too can shape what the future of housing in America will look like. We too have a choice.

The suburbs are far from perfect. And they aren’t going away anytime soon. This isn’t an excuse to ignore what’s wrong with them, but rather a burning imperative to change them, to improve upon what we have instead of throwing in the towel and accepting things as they are.

Sign up to receive ONE-KEY™ news and updates.

Editorial Note: This article was brought to you courtesy of Rose Morrison, managing editor of ...

Editorial Note: This article was brought to you courtesy of Rose Morrison, managing editor of ...

Editorial Note: This article was brought to you courtesy of Rose Morrison, managing editor of ...